Rey brillante de la música country, el tema del día.

Rey brillante de la música country

La diseñadora de moda Nudie Cohn, una judía nacida en Ucrania, le dio a la música country su característico brillo de diamantes de imitación.

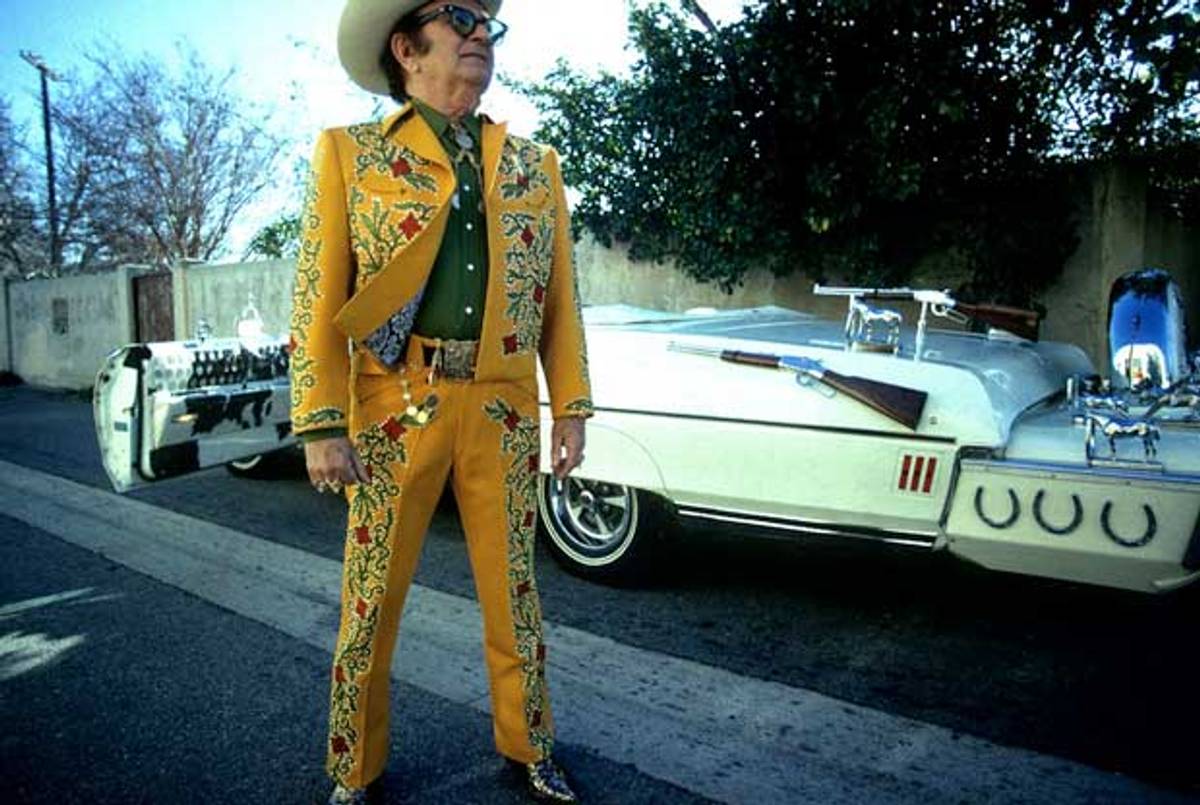

Nudie Cohn (Mike Salisbury)

El cantante Glen Campbell pudo haber popularizado el término "vaquero de diamantes de imitación" con su exitoso sencillo de 1975 , pero el concepto (intérpretes de música country ataviados con trajes de lentejuelas) fue inventado dos décadas antes por un diseñador cuyas raíces se encuentran a miles de millas de Nashville. Nudie Cohn, un inmigrante judío de Ucrania, fue el hombre que creó los elaborados atuendos cubiertos de pedrería que durante mucho tiempo han sido un sello distintivo de la moda de la música country.

Cuando miles de fanáticos del country lleguen a Nashville para el festival anual de la Asociación de Música Country la próxima semana, tendrán la oportunidad de ver las mejores creaciones cubiertas de pedrería de Cohn en el Salón de la Fama de la Música Country. Cohn diseñó trajes para leyendas de la música country como Hank Williams, Gene Autry y Johnny Cash, así como para el mismo Campbell. El trabajo de Cohn luego ayudó a inspirar un movimiento que redefinió el sonido country con artistas como Wilco y Ryan Adams. No estaba encajonado por géneros musicales: le dio a Elvis Presley uno de sus looks más icónicos. Y muchos artistas muy alejados del género country se han ido al nudie a lo largo de los años, desde ZZ Top hasta Cher y Tony Curtis, mientras que " Nudie se adapta a” se han mantenido geniales entre los músicos que definieron generaciones que desafían los límites musicales, desde Bob Dylan hasta Jack White. Pero el look sigue siendo un clásico vaquero icónico, ante todo.

Si bien muchos artistas pueden reclamar una medida de crédito por darle a la música country su sonido, un solo hombre puede reclamar la mayor parte del crédito por darle a la música country su apariencia, como lo deja en claro la exhibición.

***

In 1913, Nuta Kotlyarenko was sent away from his home in Kiev by his parents, who hoped to save their child from the frequent Ukrainian pogroms. He was 11 years old, and the only skills he had were learned from his time as a tailor’s apprentice. His family, like so many other Eastern European Jewish families, was involved in the clothing business: His father was a boot maker who felt the garment business held more promise for his son than his own trade. When the young boy arrived at Ellis Island, his last name was shortened to Cohn, and the immigration official didn’t know how to spell his first name, so he wrote “Nudie” on his papers instead, and the name stuck.

“He came to New York with his brother, Julius,” said Cohn’s granddaughter Jamie Lee Nudie, who changed her own last name to her grandfather’s first name as a tribute to him. “Julius was older and interested in girls and sort of let my grandfather fend for himself.” She told me that her grandfather’s early years in the United States were lonely, and he spent a lot of time at movie theaters: “He’d go and watch the old westerns.” Cohn idolized the cowboys he watched on the big screen, she said, and it was during those hours spent watching his silver-screen heroes that he realized that there was something missing from the costumes worn by the frontier gunslingers and outlaws.

The early 1930s found Cohn doing something familiar to many Americans during the Great Depression: roaming the country, looking for work. He held odd jobs shining shoes, tailoring, and even trafficking narcotics—a job that landed him behind bars in Leavenworth. When Cohn was released, his path down the straight and narrow led him to a boarding house in Mankato, Minn., where he met Bobbie Kruger. The two married in 1934, had their only child, Barbara, and moved to New York City, where Cohn and Kruger started their first business: making G-strings for local burlesque queens and selling them out of their store near Times Square, Nudie’s for the Ladies.

In the 1940s, the Cohns relocated to Hollywood. They set up shop in the garage of their home, making garments for everybody in Hollywood from actors to showgirls. Then, in a fitting twist of fate, the cowboys Cohn had grown up idolizing came calling, and he became the best-known tailor for country-western singers making their way through California.

By the end of the decade, Cohn had the reputation as the area’s premier tailor for country wear, and he opened Nudie’s of Hollywood on the corner of Vineland and Victory in North Hollywood. Out of his store, Cohn did it all: from three-piece suits to the more traditional western shirts that had been popularized by singing cowboys like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. Rogers was so impressed by Cohn’s designs that he asked Cohn to design many of the colorful western shirts that he and his wife Dale Evans wore on their popular television program, The Roy Rogers Show.

Working for “The King of Cowboys” made Cohn famous, but when musician Lefty Frizzell approached him in 1957 to create something that would help him stand out on bills featuring larger acts, Cohn inadvertently crafted his own legacy as a designer by spelling out Frizzell’s initials in blue rhinestones. In retrospect, it seems like a simple idea: If you want to draw attention to something, make it bright and shiny. But according to his granddaughter, Cohn was the first person in country music to apply this concept to suits, like the ones he designed for icons like Hank Williams and Johnny Cash. “He was the first person to do that,” she said. “That’s how it got started.”

There’s very little evidence to dispute her claim. Nathan Turk, also a Jewish immigrant tailor who specialized in western wear, put rhinestones on many of his creations after Cohn did, but there’s no evidence of the practice that predates Cohn. And since flashy characters and loud suits dominated postwar country, Cohn’s sparkle and shine helped him become the most important tailor in all of country music.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Cohn made suits for everybody: a black suit with lightning bolts for George Jones, a pink suit for Webb Pierce with a wandering cowboy behind jail bars on the back, and one outfit for Marty Robbins that the Country Music Hall of Fame’s curatorial director Mick Buck called “one of the most colorful and mind-blowing designs I’ve seen from a rodeo tailor”—it’s also Buck’s personal favorite in the museum’s collection, which he recently curated for an exhibition of Cohn’s work, “Silver Threads and Golden Needles: Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors.” Buck is fast to point out that while Cohn was known for making “over the top” designs, he could just as easily create simple, elegant suits, like the pinstripe number Cohn made for Hank Williams that’s on display at the museum. But Cohn’s most famous work might be the $10,000 gold lamé suit he created for Elvis Presley, which the King wore on the cover of his 1959 album 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong.

By the 1960s, Cohn’s colorful suits were part of the country-music establishment. Nearly every major star that graced the Grand Ole Opry stage owned at least one Nudie Suit, and in 1963, Cohn moved the store to a larger North Hollywood location on Lankershim Boulevard. That same year, after attending his wife’s church for decades, Cohn converted to Christianity—much to the dismay of his Jewish family—but his granddaughter insists that Cohn never denied his roots: “He had a necklace that I have now, and it has a Jewish star on there and a Christian cross on it. He was unique.”

Cohn’s work was legendary by the end of the decade. He even translated his trademark look onto other products: Cohn got into the custom car business, tricking out Cadillacs and Pontiac Bonnevilles into Nudie Mobiles with Texas longhorns on the hood, leather interiors embroidered with wagon wheels, and saddles instead of children’s car seats.

The Nudie Suit was introduced to a whole new generation in 1969, when Gram Parsons and his band the Flying Burrito Brothers donned custom suits on the cover of their album The Gilded Palace of Sin. While it never achieved commercial success, the album picked up where Parsons left off as a member of the Byrds on their groundbreaking fusion of rock and country music, Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Today, Gilded Palace is cited as one of the most important records in the sub-genre critics have dubbed alt-country. Elvis Costello, Steve Earle, and Beck have all named the record as a major influence, and a few years after its release, the Eagles sold millions of albums using the template created by Parsons and his contemporaries. But as iconic as the tracks on the album are, the image of the singer decked out in his white Nudie Suit with marijuana leaves and amphetamine pills made out of rhinestones is what remains most closely associated with the Parsons name. “Gram was a big aficionado of early country music,” said Parsons biographer Jessica Hundley. “He knew about Nudie through all the singing cowboys.”

Parsons’ impetus for working with Cohn was to celebrate everything he loved about both old-time singing cowboys and California culture, a look he dubbed “Cosmic Americana.” Hundley calls the look “an embrace of classic with a psychedelic edge,” which became part of the Gram Parsons legend. “Nudie,” she said, “was the embodiment of that presentation.”

Parsons’ influence on his friend Keith Richards is most noticeable on the Rolling Stones 1972 masterpiece Exile on Main Street, but a year after the record was released, Parsons died at 26 from an overdose of morphine and alcohol. As a tribute to his friend, Richards donned a custom Nudie Suit for numerous shows during the Rolling Stones’ 1973 European tour. The red suit was embroidered with sunsets, cactus flowers, snakes on the pant legs, and flying saucers—a reference to the 1947 UFO sightings in Roswell, N.M. In 2010, the suit sold at auction for $21,875.

Cohn passed away in 1984; Dale Evans gave the eulogy at his funeral. His store remained open until 1994, run by his widow and his granddaughter. Since then, Jamie Lee Nudie has kept her grandfather’s legacy alive by acting as the family historian and keeping the Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors website updated with information about opportunities for fans to see Cohn’s work.

Cohn’s suits remain cemented in country culture long after his death, even as styles have changed. By the 1980s and early ’90s, black became all the rage in country music, as singers like Garth Brooks and Brooks & Dunn sold millions of albums while clad in black cowboy hats and matching black shirts. But while mainstream country fashion got less flashy, the burgeoning alt-country scene preferred the look of Parsons, and Nudie Suits were a big part of that equation. In a 1993 interview, Jay Farrar of the band Uncle Tupelo (and later of Son Volt) mentioned that he loved Parsons’ Nudie Suits and thought he was a “snazzy dresser.” Eventually there’d even be a band called the Nudie Suits.

Cohn’s style endures as a family tradition, thanks in large part to Jamie Lee Nudie and Manuel Cuevas, Cohn’s onetime head tailor and former son-in-law. After divorcing Cohn’s daughter, Cuevas created the roses and skeletons insignia of the Grateful Dead and supplied the suits for the Beatles during their Sgt. Pepper phase. After the divorce, Cuevas moved to Memphis, created his own brand, and opened his own shop, and eventually his son (Cohn’s grandson), Manuel Cuevas Jr., got in on the act: In 2008, Wilco appeared on Saturday Night Live with lead singer Jeff Tweedy in a white suit covered in embroidered roses—designed by Cuevas Jr., in an obvious nod to his late grandfather, Nudie Cohn. Wilco, a band that has captivated contemporary alt-country fans and sold hundreds of thousands of records to date, paid homage to Cohn in front of millions of people on one of network television’s biggest stages.

Cohn’s legend and his suits haven’t become relics of another time; today, they’re valuable collectibles for some and inspiration for others. Just last year, American Idol contestant Paul McDonald wore a Cohn-inspired suit, created by none other than Cuevas Jr. The Nudie Suit has become a symbol for country’s past and an icon for contemporary musicians besotted with Americana and its history—all this from the work of a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe who thought his cowboy heroes could use a little sparkle.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jason Diamond is the literary editor of Flavorwire and founder of Vol. 1 Brooklyn. His Twitter feed is @imjasondiamond.

Jason Diamond is the literary editor of Flavorwire and founder of Vol. 1 Brooklyn. His Twitter feed is @imjasondiamond.

¡Únete a nosotros!

Todas las últimas noticias de Tablet, en su bandeja de entrada, todos los días. Suscríbete a nuestro boletín.